A Connected Critic

Can Michael Walzer Connect High-Modernity with Tradition?

I. MORAL PLURALISM

- A. The Radicalization of Universalism

- B. Abusive Universalism

- C. Reiterative Universalism

- D. Practical Particularim

A. The radicalization of universalism

Modernity is a project that strives to reshape the old pluralistic world into a uniform mode by using a standard universal rationality. Interestingly enough, the outcome of modernization in a liberal state such as the United States is anything but uniformity. What turns out, instead, is a religiously, morally, and politically pluralistic society. People living in a liberal state like this, Alasdair MacIntyre perceives, are entangled in conflicting claims devoid of rational justification. The picture he portrays is a fragmented society with fragmented selves. He attributes this phenomenon to the failure of modernity. Advocates of modernity believe in a universal rationality. But thinkers of the Enlightenment and their successors have been proved unable to reach a broad consensus of what this rationality is. They put forward a variety of conflicting answers. “One kind of answer was given by the authors of the Encyclopédie,” MacIntyre observes, “a second by Rousseau, a third by Bentham, a fourth by Kant, a fifth by the Scottish philosophers of common sense and their French and American disciples.” Each claim tries to compete with the others but without great success. Academicians are entrenched in their own positions and engaged in an endless contest. Their debates, so far, have done more harm than good, for the debaters have already determined not to be convinced by other rationalities and to meet every challenge by counter argument, yet ordinary people are confused by their arguments and become cynical to rational justification. Gradually this cynicism gives way to a kind of fideism. “Fideism has a large, not always articulate, body of adherents,” warns MacIntyre, “and not only among the members of those Protestant churches and movements which openly proclaim it; there are plenty of secular fideists.” “Consequently,” he continues, “the legacy of the Enlightenment has been the provision of an ideal of rational justification which it has proved impossible to attain.”1A. MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, Notre Dame, IN, 1988, pp. 5-6.

The unsettling American public life has also been documented by some sociologists. They are not satisfied with this situation either, and have suggested some solutions. MacIntyre’s proposal is different: he thinks that the ultimate solution has to be found in tradition. Modernity, he argues, doubly confuses us by excluding tradition from our sight. Its overemphasis on reason and its antagonism towards tradition blind its children from seeing the impacts of tradition upon their life. After having studied some prominent Western traditions, MacIntyre concludes that traditions are still present in liberal society, though often in fragmented and disguised forms. He reports that “it is indeed a feature of all those traditions with whose histories we have been specifically concerned that in one way or another all of them have survived so as to become not only possible, but actual, forms of practical life within the domain of modernity.”2A. MacIntyre, Whose Justice?, p. 391. Furthermore, people mix liberalism and fragments of traditions in their own ways: “they tend to live betwixt and between, accepting usually unquestioningly the assumptions of the dominant liberal individualist forms of public life, but drawing in different areas of their lives upon a variety of tradition-generated resources of thought and action, transmitted from a variety of familial, religious, educational, and other social and cultural sources.”3A. MacIntyre, Whose Justice?, p. 397. On the whole, the citizens of liberal states are neither liberal nor traditional. They live in a liberal social framework while unknowingly choose a combination of human values from different traditions. According to MacIntyre, a tradition that embraces rational enquiry as a constitutive part can provide people with a coherent understanding of their relationships with society and nature. Modernization has deprived us of our consciousness of tradition, and thus, of a way to the wholeness of life. Only by anchoring oneself to one particular tradition and engaging in dialogue with rival traditions can one overcome the drawback of the unfinished and unfinishable modernity.

MacIntyre’s proposal, though sounds plausible, is only a hypothesis. We have to wait and see how the project will be substantiated before giving our final judgement. Nevertheless, we can foresee the formidable, if not insolvable, problem of plurality, that is, how to construct, from the perspective of a particular tradition, a common morality, which will be accepted by other fellowcitizens holding other traditions. MacIntyre is not optimistic of finding a compromise among the traditions; he would probably just find a pot-au-feu of traditions so distasteful that he would never recommend it. He hints that the final solution must come as a result of the competition between rival traditions. In the end, only the fittest tradition will survive.

Another solution is to select a popular theory as the basic theoretical framework, and then brings in other theories as corrections so as to produce an improved version. Hopefully, the amalgamated programme will appeal to a wider audience. This strategy is adopted by John Rawls. In the preface of his Theory of Justice, Rawls underlines that utilitarianism has been the “predominant systematic theory” in modern moral philosophy. Since the great utilitarians such as Hume, Adam Smith, Bentham, and Mill were both social theorists and economists of the first rank, the moral principles they worked out could be fitted into the comprehensive scheme of political economy.4J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice, rev. ed., Cambridge, MA, 1999, pp. xvii-xviii. Unfortunately, many utilitarian implications clash with our moral sentiments. One of the basic flaws often criticized is that the application of the theory often results in unfair distribution of goods, even though it intends to treat people justly. The utilitarian, as one critic succinctly sums up, “allows one person’s happiness to compensate for another’s misery.”5P. Pettit, Judging Justice. An Introduction to Contemporary Political Philosophy, London, 1980, p. 135. Pettit also gives an unhappy incident showing that treating people as equals in the utilitarian mould means treating them unequally (ibid., pp. 130-131). With the intention to replace utilitarianism, Rawls sets out to reformulate a social contract theory based on the works of Locke, Rousseau, and Kant. First of all, Rawls affirms that every person has some basic rights and liberties which are inviolable and untradable. But he also recognizes that inequality is a persistent social phenomenon. In order to account for the differences among people, he allows some inequalities on condition that the benefit of the least-advantaged will be maximized. Based on the model of Kant’s categorical imperative, Rawls invents the Original Position. Then, by using “the English economics,” he shows that “good will” coincides with “practical reason”—both of them endorse the difference principle. The purpose of this synthesis is to provide a workable framework for a liberal society. “My hope,” Rawls declares, “is that justice as fairness will seem reasonable and useful, even if not fully convincing, to a wide range of thoughtful political opinions and thereby express an essential part of the common core of the democratic tradition.”6J. Rawls, A Theory, p. xi. As a matter of fact, Rawls’s enterprise has been widely praised, and his moderate objective has, to a certain degree, been realized.

Not everyone agrees with Rawls, though. MacIntyre would probably not accept his theory, and Walzer has constructed a new theory of justice to rival his. Looking from the perspective of MacIntyre, Rawls’s proposal is at best a working theory that provides a modus vivendi. It scarcely touches upon the problem of how a person in late-modern society can respond to tradition and multiculturalism. On the other hand, MacIntyre’s solution appears to be backward-looking. He proposes to return to tradition, but he has not sufficiently considered the present conditions. It seems that he is not sensitive to the “arrow of time,” which carries society along an irreversible path.7The term “arrow of time”, which is explained in chapter 3, comes from Ilya Prigogine. Cf. I. Prigogine & I. Stengers, Order out of Chaos. Man’s New Dialogue with Nature, London, 1984; I. Prigogine, The End of Certainty. Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature, New York, NY, 1997. A better approach would be one that connects the present conditions with the past, and at the same time looks forward to the future.

Walzer is a connected forward-looking social theorist. By taking a long view, he perceives the present problem from a historical perspective, and proposes a solution which is a reasonable historical development of the past. One of the techniques he employs in finding the new directives can be summed up as the radicalization of modernity. He takes up the doctrines of modernity and uses them to measure modernity itself. If the standards of modernity are strictly applied to modernity, it will give quite astonishing results. For instance, if we apply universality to universalism, the result will be a pluralism.

Kant formulates the universal rationality as the categorical imperative: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”8I. Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, in J. W. Ellington (trans.), Ethical Philosophy. The Complete Texts of Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals and Metaphysical Principles of Virtue, Indianapolis, IN, 1983, p. 30. Kant’s universal rationality involves an act of will. By willing it universally, I decide that other people will it too. Undeniably, the success of modernization rests on imposing a unified will on society and the environment alike. But this is only half of the modern art. The other half relies on the ability to adjust one’s will in response to the reactions of the others. In science, we do experiments and use the data to modify our theories. In politics, we set up democratic system and accommodate the preferences of the people. This mechanism is commonly called “reflexivity.” Rawls takes up reflexivity in philosophy too. He claims that he is using the method of “reflective equilibrium”—that is, by going back and forth between principles and moral judgements—to formulate his two principle justice.9J. Rawls, A Theory, p. 18. Nevertheless, one may still criticize his primary aim. His philosophical intuition for unity, one may say, has overcome his reflexivity so that he fails to reflect upon the proposition of a single unifying principle. He wills to find a simple set of universal principles. But could this adequately accommodate the complex and often conflicting moral opinions of peoples? Reflexivity requires us to doubt even the fundamental tenet.

In reality, we have a variety of rationalities. There never exists a single universal principle that rules over the world of opinions regardless of time and space. This phenomenon is probably due to the fact that human beings are creative. We have commonalities because of our human nature, and we have differences because of our creativity. It thus follows that what is really universal is not our rationality but our commonalities and differences. Walzer takes this position as his point of departure. He says, “We are very different, and we are also manifestly alike. Now, what (complex) social arrangements follow from the difference and the likeness?”10M. Walzer, Spheres of Justice. A Defense of Pluralism and Equality, Oxford – Cambridge, MA, 1983 (repr., 1996), p. xii. The proposal he gives is a moral pluralism that can accommodate both universality and particularity.

B. Abusive universalism

The struggle between moral universalists and moral relativists has a long history. Both sides have had their own faithful adherents and outstanding spokesmen. Sometimes one camp gains the upper hand, and sometimes the other. But so far, neither side has won a complete victory. It seems that the debate will go on and on without a foreseeable end. Walzer is reluctant to go into this battleground for fear that once inside, there will be no way out. His interest lies more in the practical moral issues: how to make moral decision, what justice requires here and now, when to intervene, etc. Nonetheless, as an ethicist, Walzer can hardly ignore the issue that the universalists and the relativists are struggling for. He recognizes that universality and particularity will always be two permanent features in morality, but he does not conceptualize them from either the universalist or the relativist perspective. He chooses to look at this problem afresh—from the standpoint of making practical moral decision. Thus, the question for him is no longer whether morality is relative or universal, but rather how to give a reasonable explanation to the two seemingly antithetical phenomena displayed in morality.

Walzer is sympathetic to the relativist claim that morality is uniquely connected with a particular society, which is prima facie a historical reality. Such historicity has always been the Gordian knot for the universalists, who have long tried to transcend it by various means. The pragmatic response, for Walzer, is neither transcending particularity nor denying the universality of humanity, but to find out their functions in practical moral reasoning. He thus allocates universality to international justice, and particularity to domestic justice. If each of them is confined to its own domain, there will be no more conflict. To distinguish himself from the universalists and the relativists, Walzer calls himself a “particularist.”11See M. Walzer, A Particularism of My Own, in Religious Studies Review 16 (1990) 193-197. His argument for particularism consists of two main parts: a refutation of universalism and a harmonization of particularity and universality. It is important to lay out Walzer’s criticism beforehand in order to explain his apparent favouritism towards particularity. He has two good reasons to disparage universalism. First, universalism is often used by aggressive countries as a cover to stage an attack on another country or to expand their territories. Second, universalism leads to a single-minded pursuit of simplicity, which overlooks the complexity of the real moral world. The undesirable elements in universalism stem from two sources: one from Judaism, and the other from Greek philosophy. In what follows we will look into them separately and then explore their misuses.

1. Jewish religion

Judaism can be interpreted as a universal religion.12Judaism may have gone through various stages of development before it finally produces a monotheistic theology. But I would refrain from discussing its history here. In its creation narrative, the God of Israel is described as the creator of the universe. He creates the world in six days, and assigns a function to every creature he brings into existence. Thus the world is transformed from the primordial chaos into an ordered paradise where men and women stage their adventure. Among the nations on earth, God chooses Israel, and gives them the Law. They are to live as a kingdom of priests, a holy nation, and a light unto the world. One God, one Law, one Chosen Nation, these three make up a seedbed for universalism. Generally speaking, universalism means a comprehensive view of the whole. But there can be many equally valid views of the unity, and thus different versions of universalism. In fact, the canons of Judaism and Christianity themselves have already contained different kinds of universalism.13For discussions of different kinds of universalism, see J. D. Levenson, The Universal Horizon of Biblical Particularism, in M. G. Brett (ed.), Ethnicity and the Bible (Biblical Interpretation Series, 19), Leiden, 1996, 142-169; J. M. G. Barclay, Universalism and Particularism. Twin Components of Both Judaism and Early Christianity, in M. Bockmuehl & M. B. Thompson (eds.), A Vision for the Church. Studies in Early Christian Ecclesiology in Honour of J. P. M. Sweet, Edinburgh, 1997, 207-224. As it is not our purpose here to explore the various kinds of universalism, we shall focus only on a specific universalism which has dominated the Western world. Walzer calls it the “covering-law universalism.” This universalism, as Walzer elegantly articulates, “holds that as there is one God, so there is one law, one justice, one correct understanding of the good life or the good society or the good regime, one salvation, one messiah, one millennium for all humanity.”14M. Walzer, Nation and Universe, in G. B. Peterson (ed.), The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Vol. XI, Salt Lake City, UT, 1990, 507-556, p. 510.

The notion of the covering-law universalism can be found in some prophetic books, especially in Isaiah. In one passage, we are told that the end of human history will be the final victory of Yahweh, that his holy mountain Zion will be exalted over all mountains, and that his law will prevail forever. All nations will be subdued, weapons will be destroyed, and a perpetual peace will be established on earth:15Is 2,2-4. Quoted from the King James Version. Walzer prefers this version because the early political reformers and revolutionaries used it. Therefore, I shall follow Walzer’s practice. All biblical quotations will be quoted from the King James Version unless otherwise stated.

And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it. And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

The vision of all nations going up one mountain, prostrating before one God, and walking under one Law was a hope shared among the Jews in the prophetic period, or at least among the literary élite.16P. D. Hanson, The People Called. The Growth of Community in the Bible, San Francisco, CA, 1986, pp. 312-324. It is repeated thrice in Isaiah that the servant of God will be “a light to the Gentiles.”17Is 49,6; 42,6; 60,3. Who this servant is is unclear in the texts and hence open to speculation. Perhaps he is a certain king of Judah, or a future leader of Israel. Or he is just a symbol of the whole Israelite nation, or he is indeed Jesus of Nazareth as the Christians have proclaimed. No matter who this servant is, the passages point towards a universal history: Israel is chosen not only for its own sake but also for the whole human race; the Jews are erected as the representative for all nations. It follows that only the history of Israel has meaning and significance; all the other nations are living purposelessly waiting to be enlightened. Until they go up the mountain, their life is meaningless. In this way, the theology of one god is elaborated into a universal history hinging on one nation.

It is paradoxical that the bearer of the universal history has manifested itself as an exclusive faith, the very emblem of a tribal religion. Why have most of the Jews been uncommitted to the holy mission of universalizing their creed? Walzer suggests that the doctrine of the universal history has something to do with the “experience of triumph.”18Nation, pp. 510ff. It is true that the notion of universalism is embedded in Judaism, but its elaboration and propagation require the sustained effort of its believers, who can only be motivated by pride or by a sense of victory. Since the ancient Jews lacked both, it is not surprising that Judaism has not evolved into a kind of triumphant universalism, Walzer reasons.

What the Jews did not manage to accomplish, the Christians have achieved. At the start, Christianity was merely a sect of Judaism. However it was able to break open the constraint of Jewish ethnicity by transforming the peculiar, myriad rites and laws of the Jews into universal symbols. The early Church claimed that it had fulfilled the eschatological biblical prophecy: it was now the last days, the Church was the true Israel and the heir of God’s promise to Abraham. One of the often-quoted texts which asserts this claim can be found in the letter of the apostle Paul to the church of Ephesus:19Eph 2,11-22.

Wherefore remember, that ye being in time past Gentiles in the flesh, who are called Uncircumcision by that which is called the Circumcision in the flesh made by hands; That at that time ye were without Christ, being aliens from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers from the covenants of promise, having no hope, and without God in the world: But now in Christ Jesus ye who sometimes were far off are made nigh by the blood of Christ. For he is our peace, who hath made both one, and hath broken down the middle wall of partition between us … Now therefore ye are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellowcitizens with the saints, and of the household of God.

The covering-law universalism in Christianity has basically the same form as that in Judaism except that Christ Jesus, in place of Israel, plays the pivotal role in the world history. Christ is the holy temple. Through his death on the cross, all nations are brought into mystical communion with God—the final destiny of humanity. There is no more distinction between Jews and Gentiles. By faith, people are granted equal citizenship in the heavenly kingdom. In this way, Christianity turns itself into a universal religion characterized by its zeal for mission. And the covering-law universalism, Walzer observes, attains its standard form in the hands of the Christians.

Walzer is not ignorant of the fact that in the Christian doctrine, it is the sacrifice of the Son of God rather than the law that covers all men and women.20Cf. Nation, p. 510. To the Christians, “Christ died for your sins” is a timeless truth that can be applied to any person, at any time, and in any place. Faith in Christ, nevertheless, does not destroy the law.21Cf. Mt 5,17; Jas. Christians, except for a few extremists, have never denied the relevance of the laws or the moral rules in the Bible, though which set of laws should be kept and which should be ignored vary from time to time and from community to community. To some, the Christian morals serve as the perfect codes of conduct and provide a yardstick by which the non-Christians are measured, if not publicly, at least privately among themselves. Strange though it is, they have not been led by such practice to a form of Jewish legalism, nor have they given up their claim to be the bearer of the good life and the good society.

One thing that Walzer has not clearly articulated is that the covering-law universalism is not merely a set of universally applicable moral norms. Rather, it has to be understood, and indeed more appropriately, within the framework of a particular view of world history, namely the so-called salvation history. According to this understanding, God creates the world from a plan and for a purpose. That purpose is progressively revealed in the course of human history. Yet, not every national history is significant, at least not equally significant. Only the history of the chosen people is related to the salvific plan of God, first the Israelites, then the Christians (the spiritual Israelites). God dwells among his chosen people, who see themselves as the representative of humanity and the only ones who lead a meaningful life. They call the other people gentiles or heathens, which carry the pejorative meaning of a lower humanity. The pagans are “aliens” from the commonwealth of the saints, and “strangers” from the promise of God, hence they have absolutely “no hope” unless they are converted and incorporated into the body of Christ. There is scarcely anything that the saints can learn from the history of the heathens. In short, the covering-law universalism consists of this general form: one origin, one world history, one authentic people, one law, one good life, and one mission. Such has become the standard form of universalism in the Western culture, whose different versions can be found in the Hegelian/Marxist philosophy of world history, in the social theory of progress, and in the political theory of liberalism.

2. Greek philosophy

The other origin of universalism, which Walzer frequently mentions and repudiates, is the ancient Greek philosophy. He thinks that the search for singularity and uniformity is “overdetermined” in Western philosophy, that is, the search for a single principle or a set of principles has almost been the sole task of philosophers. This, relative to the covering-law universalism, can be called the singular universalism. Walzer sees the singular universalism as one of the chief enemies of pluralism. He has devoted at least four books to counterclaim this tradition.22Spheres; Interpretation and Social Criticism, Cambridge, MA – London, 1987 (repr., 1993); The Company of Critics. Social Criticism and Political Commitment in the Twentieth Century, New York, NY, 1988; Thick and Thin. Moral Argument at Home and Abroad, Notre Dame, IN – London, 1994. He argues that plurality is a reality of our world. To subdue plurality under one single principle is to mistreat the otherness of reality; this amounts to an act of tyranny. While fiercely denouncing the singular universalism, Walzer scarcely writes about its origin. Maybe he assumes that his Western readers are already well informed of this tradition. It would be trivial to repeat what is so obvious. But those who are not well versed in Western philosophy will find it hard to understand why Walzer and his antagonists should spend so much time on this. For the sake of this group of readers, I will give a short account of the singular universalism. For those who are familiar with this subject, they may as well skip this section and go directly to the next section.

A Neo-Platonist philosopher, Dominic O’Meara, once made a penetrating remark about the deep-seated Western way of thinking: “Throughout the history of philosophy and science can be found the idea that everything made up of parts, every composite thing, depends and derives in some way from what is not composite, what is simple.”23D. J. O’Meara, Plotinus. An Introduction to the Enneads, Oxford, 1993, p. 44. He calls this idea the “Principle of Prior Simplicity.” O’Meara is right: the reduction to the simple is certainly the most important methodology in philosophy and in science. It is, however, not merely a means but also the goal of the reflective enterprise. Philosophers believe that what is more simple is more real—the simpler, the realer. The simplest is the realest substance that causes everything into being. And the ultimate reality embodies the truth, the good, and the beauty. Thus, the search for the simple is the destiny and the passion of life. We can find an extensive record on the pursuit of the simple in the writings of Plato, who first discriminates the world of sensible things from the world of Forms or Ideas. His is a philosophy of Ideas. Since Plato wrote so much about Ideas, it is advisable to begin with a summary report given by his pupil Aristotle:24Aristotle, Metaphysics, A. 6, in W. D. Ross (ed.), Metaphysica (The Works of Aristotle, 8), Oxford, 21928 (repr. 1966).

For, having in his [Plato] youth first become familiar with Cratylus and with the Heraclitean doctrines (that all sensible things are ever in a state of flux and there is no knowledge about them), these views he held even in later years. Socrates, however, was busying himself about ethical matters and neglecting the world of nature as a whole but seeking the universal in these ethical matters, and fixed thought for the first time on definitions; Plato accepted his teaching, but held that the problem applied not to sensible things but to entities of another kind—for this reason, that sensible thing, as they were always changing. Things of this other sort, then, he called Ideas, and sensible things, he said, were all named after these, and in virtue of a relation to these; for the many existed by participation in the Ideas that have the same name as they.…

Since the Forms were the causes of all other things, he thought their elements were the elements of all things. As matter, the great and the small were principles; as essential reality, the One; for from the great and the small, by participation in the One, come the Numbers.

The above passages are complicated, obscure, and at some points, inaccurate. They can nonetheless serve as a starting point for our appreciation of the Principle of Prior Simplicity at work in the thought of Plato. First of all, we are told that Plato accepts the Heraclitean doctrine that all sensible things are in a constant flux, and that what is in constant flux cannot be known. Heraclitus sees the world changing unceasingly. If something is changing continually, no true statement about it can be made. Thus he concludes: “it is impossible to step twice into the same river.” The reason is that the river which the person first stepped into has changed—it will never remain the same river. Cratylus even pushes this logic to its extreme to say that “one could not do it even once.”25Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1010a 12. Plato, however, believes that in contrast to the contingent things, there exist some eternal entities which do not change. The former, we can hold opinions about them, whereas the latter, we can speak of true knowledge.26Cf. D. Ross, Plato’s Theory of Ideas, Oxford, 1971, pp. 124-125.

Of his eternal entities, Plato takes inspiration from his mentor Socrates’ search for definitions on moral matters such as pious and impious, noble and ignoble, just and unjust, sanity and insanity, fortitude and cowardice. He regards these not merely as definitions or names but entities of another kind which can only be grasped by reason alone. He calls them Ideas, or Forms. Since Ideas are pure and unchangeable, they are simpler than their related sensible things. And what is composite must own a simpler source. Therefore, sensible things (rather than Ideas) are names of Ideas, and they derive their existence by their participation in the Forms. In the words of Aristotle, “the many existed by participation in the Ideas that have the same name as they.”

Consider the famous parable of the cave which depicts the contrast between the world of sense perception and the world of thought. Plato asks us to imagine a cave with a long and steep tunnel leading to the outside world. Inside this dark cave, there are some human creatures who have been chained from their childhood so that they can neither move nor turn their heads around. The only thing that they can see is the wall directly in front of them. Suppose a fire is burning high up behind them, and people carrying objects of different kinds walk between the fire and the prisoners. The light from the fire will cast the shadows of the objects onto the wall. Under such circumstances, the prisoners will certainly mistake the shadows as the real passing objects. They will, if they can talk to each other, give names to the shadows which are actually the names of the objects.27Plato, Republic 7.514ff. Plato uses the analogy of shadow and its object to illustrate the relationship between sensible things and Ideas. Sensible things are only shadows of the Ideas. Out of one Idea come the many imperfect material copies. By this, Plato tries to demonstrate that we are the prisoners of our sense perception. We take what we see or hear as real. But in fact, there is something more real than the sensible things. These things belong to the world of Ideas which can only be seen through the light of reason. The world of Ideas is more real than the world of sensible things and hence superior to the latter. According to Plato, most people dwell in the world of senses, only a gifted few can ascend to the world of eternity.

Plato does not stop short at applying the Principle of Prior Simplicity to the reduction of sensible things to Ideas. He wants to find the ultimate cause. Influenced by Pythagoras, he believes that numbers are the causes of the reality of other things, including Ideas. The numbers that Plato has in mind are the integers starting from 2 ad infinitum. In his time, number denotes plurality and thus 1 is not a number but the first principle of number.28Cf. D. Ross, Plato’s Theory, pp. 178-182. Neither are the numbers sensible numbers or numerable groups (groups of two, three, four, …, entities) nor abstract numbers or mathematical numbers which mathematicians manipulate without regard to any particular groups of things. They are, instead, ideal numbers which are universals, and things that are referred to as twoness, threeness, fourness, etc. They are the formal causes of other Ideas. Somehow every Idea shares the Idea of a particular number. For example, 4 is the formal principle of justice for justice involves two persons and two possessions to be exchanged.

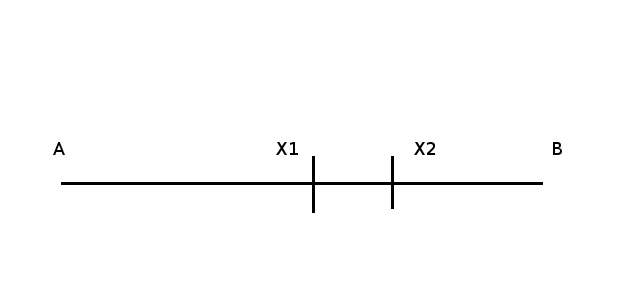

Numbers, Plato further proposes, are derived from two principles: the One and the indefinite dyad. The One is oneness, the Idea of one. As we have mentioned above, 1 is the first principle of number. For Plato, this principle alone cannot generate numbers. A second material principle is needed—the great and small, that is, the indefinite dyad.29Aristotle interprets the dyad as “the great and the small” which are actually two principles. Whereas Plato’s original meaning is “the great and small,” which is one principle having dual characteristics. Cf. D. Ross, Plato’s Theory, p. 184. The great and small is the principle of division and comparison. Imagine a finite line with two ends. We first divide it into two equal halves. Then we continue to cut the line in a certain ratio so that the point of division is always on the right side of the divided parts. Gradually the first segment will become greater and the second smaller. Theoretically this process can go on without end. The One combining with the dyad brings forth all integers.30Aristotle speaks of all numbers except prime numbers, this is probably wrong. For discussion, see D. Ross, Plato’s Theory, pp. 187-205. The generation of numbers has various interpretations and models, and the one given by David Ross is perhaps the best. To illustrate this philosophical doctrine, let us use a segmented line as below:

Suppose AB is bisected at the mid-point X1. Then we can compare the length of AX1 to that of X1B. Given the Idea of One, we can say that the length of AX1 to that of X1B is in the ratio 1:1. In effect this transforms the ratio of AB to X1B into 2:1, thus generates the number 2. If then AB is divided at X2 in the ratio of 2:1, the resultant ratio of AB to X2B will be 3:1, which gives us the number 3. The process can continue until all numbers are generated.

Plato’s search for the ultimate cause does not end in one single principle. To him, the creation of other beings from one source without the aid of a second agent of a different kind is inconceivable. It was not until Plotinus, a Neo-Platonist, that the quest for singularity reached its completion. While accepting Plato’s teaching that sensible things come from Ideas and that Ideas from the dyad and the One, Plotinus, nevertheless, holds that there is a first and ultimate principle of reality from which all other beings come, either directly or from the beings in between (that is, the beings originated from the One). In one passage, we are told that the multiplicity are emanated from the One:31Plotinus, Enneads, V. 1[10]. 6. 3-9, trans. A. H. Armstrong, Cambridge, MA, 1984.

For the soul now knows that these things must be, but longs to answer the question repeatedly discussed also by the ancient philosophers, how from the One, if it is such as we say it is, anything else, whether a multiplicity or a dyad or a number, came into existence, and why it did not on the contrary remain by itself, but such a great multiplicity flowed from it as that which is seen to exist in beings, but which we think it right to refer back to the One.

Plotinus reads Aristotle’s report as if it were saying that for Plato all things come from the One. The indefinite dyad is not an independent principle but one that depends on the One. Indeed, Plotinus has constructed a hierarchy of beings as follows: the One emanates the dyad; together they generate the Forms and Numbers, that is, the Intellect; the Intellect produces the soul in a way similar to the birth of the dyad; finally, the soul brings forth all material beings.32Cf. D. J. O’Meara, Plotinus, pp. 60-69. We have to notice that the One under the interpretation of Plotinus is no longer Plato’s Idea of one. The One is lifted out of the Forms and treated as the first and ultimate source of reality. Why did Plotinus do this?

The answer has to be sought in Plotinus’ zeal for priority and simplicity. The idea of prior simplicity, according to Plotinus, can have two applications with respect to the sequence of causes and to the composition of beings. Plotinus believes that the cosmos has a hierarchy with the ultimate cause at the top, and then the second causes, then the third causes, and so on. “If there is anything after the First,” he says, “it must necessarily come from the First; it must either come from it directly or have its ascent back to it through the beings between, and there must be an order of seconds and thirds, the second going back to the first and the third to the second.”33Plotinus, Enneads, V. 4[7]. 1. 1-5. What Plotinus perceives is a cosmos of ordered beings with different ranks. The first is the cause of the seconds, and the seconds the thirds. Between them, there are clear lines of distinction. It is, no doubt, a caste cosmos. Plotinus also contemplates that within the first caste, a monarchy is most appropriate to its magnificence; an oligarchy does not match the perfection of the first cause since the members of the oligarchy will inevitably share power among themselves and result in degraded nobility for each of them. In order to argue for the singularity rather than the plurality of the first cause, Plotinus appeals to the reduction of things to their simplest form. He says, “For there must be something simple before all things, and this must be other than all the things which come after it, existing by itself, not mixed with the things which derive from it, and all the same able to be present in a different way to these other things, being really one, and not a different being and then one; it is false even to say of it that it is one, and there is ‘no concept or knowledge’ of it; it is indeed also said to be ‘beyond being’.”34Plotinus, Enneads, V. 4[7]. 1. 5-11. For any sensible thing, we can divide it until we obtain the simplest indivisible element. But for the simplest element or the One, it is beyond our comprehension. It is said to be “beyond being,” so it is nonsense to count it as one or two or three. Otherwise, it would be captured by the Ideas of number and reduced to the same order as the Intellect or to the orders below. Therefore, the One must be the simple and the first of all.

Being the simple and the first is the source of all goods: power, beauty, values, etc. Human beings, as Plotinus sees it, are souls dwelling in bodies. As souls, we are given the task to organize and perfect material existence. If, however, we indulge in material things and forget our true nature, we will become ignorant, evil, and unhappy. The way to prevent us from falling into vice and misery is to look up to the One. To achieve this, we might distinguish three stages: (1) return to one’s true self as soul, (2) attain the life of the Intellect, (3) be united with the One.35Cf. D. J. O’Meara, Plotinus, pp. 103-106. It does not serve our purpose here to dwell further on Plotinus’ methods. Suffice it to say that the search for a unifying principle is not merely a methodology but the ultimate goal of life and the mystical desire for union with the origin. Neo-Platonists affirm this ideal, and some Christians as well. But I am not sure to what extent modern philosophers aspire to it.

3. Cover and ideal

At the core of both covering-law universalism and singular universalism lies the intuitive notion that the multitudes have a single origin. While this tenet may be true, Walzer warns that the two universalisms have developed into a form that can be used as a cover for a multitude of sins. Covering-law universalism naturally instils a sense of pride in its heirs. Since there are always people who know and keep the law and those who do not, the law can be used as a sieve to sift people into two distinct groups. And since the universal law is transcendent, the knowers and keepers tend to see themselves as superior. This attitude, though normally prohibited under the covering law, is clearly expressed in words like “the chosen,” “the people of God,” “the true believers,” and “the priestly nation.” Walzer concedes that some keepers could truly renounce the thrill of pride, but they would still have “confidence.” They are confident that their legal code is true and universal, and that they are living in the way of life which some day all men and women will imitate. “Confidence,” Walzer says, if not “pride,” is the most appropriate state of mind and feeling of such people.36Cf. Nation, pp. 512-513.

Singular universalism, likewise, instils a sense of superiority into its possessors. Philosophers commonly believe that they themselves are intellects, and thus possess special rational power for knowing things that are more real than the sensible things which ordinary people know. They have exclusive access to eternal knowledge; the laity, by contrast, merely hold contingent and accidental opinions. Plato, in his argument for aristocracy, accentuates the supremacy of the intellect. In the parable of the shipmaster, he writes: 37Plato, Republic 6.488B, quoted from Plato’s Republic. Translated with an introduction by A. D. Lindsay, London – New York, NY, 1935 (repr., 1969).

Conceive something of this kind happening on board ship, on one ship or on several. The master is bigger and stronger than all the crew, but rather deaf and shortsighted. His seamanship is as deficient as his hearing. The sailors are quarrelling about the navigation. Each man thinks that he ought to navigate, though up to that time he has never studied the art, and cannot name his instructor or the time of his apprenticeship. They go further and say that navigation cannot be taught, and are ready to cut in pieces him who says that it can.

A ship in the hands of untrained sailors will be disastrous. A democratic state, to Plato, is like a ship without a skilful master. The ship of democracy will finally fall into irrational and dangerous hands. A state as such will certainly result in chaos and turmoil. The majority rule is not a good form of government. A state requires a competent master for its steering. Politics, according to Plato, is a τέχνη which is far more complicate than any other trade or skill. Only philosophers possess the specialized knowledge of politics. Hence a city or a state should, ideally, be ruled by a philosopher-king.

Covering-law universalism and singular universalism, different though they are, are not incompatible. Of course they may work against each other, for covering-law universalism lays its claim on revelation, while singular universalism on reason, and reason may challenge revelation as it has done before. But sometimes, covering-law universalism may espouse singular universalism in perfect harmony. Theologians have put reason in the service of faith. Through the use of reason, covering law can be proved to be true and universal, and hence should be acceptable to every reasonable man. However, the roles of master and servant have been reversed in the age of reason. With respect to the covering law, since it has been widely accepted and institutionalized, it can serve as the basic source from which one formulates a more abstract set of unifying laws. Once an abstract principle is formed, it will be separated from its original context, and new meaning can be given to it by its inventor. This form of abstraction has proved to be a powerful ideational means for the reorientation of the social world. Some grand narratives are actually created thus, for example, the derivation of the Marxist historical materialism is derived from Christian teleology. Because covering-law universalism and singular universalism, either working separately or in joined forces, inspire confidence and superiority, they can be used as a perfect cover for the will to power.

Some philosophers have classified people into two groups according to their dominative trait. “If we consider the objects of the nobles and of the people,” Machiavelli writes, “we must see that the first have a great desire to dominate, while the latter have only the wish not to be dominated … to live in the enjoyment of liberty.”38N. Machiavelli, quoted in Nation, p. 537. Given that Machiavelli is correct, the world can thus be dichotomized into nobles and plebeians, or as it were, masters and slaves. The psychological state of the nobles is characterized by the will to power. Imagine that the nobles inhabit a society ruled by covering-law universalism or singular universalism. Though the law will inhibit their actions, it will also enhance their appetite for power. The will to power definitely finds “confidence,” “pride,” or “superiority” desirable. These qualities are ideal virtues of nobility. Besides, the covering law, or the singular law, or the singular covering law, can be shaped, through the magic hand of the propagandists, into a powerful ideology for domination—either to exploit their own society or to conquer other nations.

Covering-law universalism and singular universalism are theories of unification. The former imposes a system of laws on the people and the latter a set of principles. They bind people to some so-called objective and transcendent laws. Discrepancies in social behaviour can then be curbed by banning the unwanted acts as outlawed or irrational. Moreover, universal laws usually prescribe a social hierarchy. Walzer calls it “the social version of the gold standard.” It has the appearance that “one good or one set of goods is dominant and determinative of value in all the spheres of distribution.” “And that good or set of goods,” he continues, “is commonly monopolized, its value upheld by the strength and cohesion of its owners.”39Spheres, p. 10. A monarch, or an oligarchy, or a class who monopolizes the dominant good can effectively control the whole society.

The legitimization of the monopoly of a dominant good constitutes an ideology. Aristocracy is the principle that the best-born or the most intelligent rules; this group usually monopolizes land and familial reputation. Theocracy is the principle of those who possess or know the revelation of God; they are the monopolists of divine grace and office. Meritocracy is the principle of careers open to talents; they monopolize knowledge. Free exchange is the principle of risk-takers who are ready to wager their money; they are the monopolists of movable wealth. These groups compete with each other and struggle for supremacy. The struggles take place in a paradigmatic way. Whenever a group wins, it will work out a systematic conversion of the dominant good into all sorts of other goods. The principle of monocracy prevails, although government changes from monarchy to oligarchy, and then to democracy. A single principle instead of a single person becomes the key player in modern politics. In totalitarian Marxist states, political power intrudes into every aspect of life and maintains cohesion by coercion. While it is true that people have freedom in the capitalist world, the exercise of liberty is dependent on how much money one possesses. The principle of free market is working everywhere. It infiltrates people’s life. Our educational system, for instance, is on the whole programmed to produce effective competitors in the arena of the market, and our social system is geared to facilitate its proliferation.

Both kinds of universalism have an internal moral compulsion to extend their influence to the whole globe. Confidence, pride, or superiority cannot be contained within a territorial boundary either. Conceivably there are noble nations as well as plebeian nations. The noble nations, similar to individuals, would always try to conquer, to command, and to rule, while the plebeian nations would be content living within their own territory free of external intervention. If a noble nation inherits any one or both of the universalisms, its ambition to expand will easily find moral justification, even moral imperative. Covering-law universalism or singular universalism puts forward a legal code or moral principle claimed to be true and applicable everywhere. The noble nation itself serves as the model for all nations to imitate: what it possesses, the other nations must acquire. But how are other nations to adopt the noble ideal which they have never heard? And how are they to hear without a messenger? Now, men have to be sent, and the noble nation becomes, in Walzer’s word, a “nation-with-a-mission.”40Nation, p. 540.

This conception disparages the experience of the nations that do not keep the law. Because they do not know the law and because they do not keep the law, their life is meaningless, or at least, insignificant. The noble nation brings salvation, so to speak, to them. And many nasty things can be justified for the ultimate good that the salvation will bring. Envoys are first sent to teach the law. If the plebeian nations refuse to accept it as they usually do, military can then be sent to enforce the law. Occupation and domination are thus seen as the inevitable processes in the way of actualizing the universal law and civilizing the world.

The above description is not merely a possibility. Walzer once bravely pointed out to the Oxonians that imperialism had actually argued as such. Consider these lines from Rudyard Kipling’s “Song of the English”:41R. Kipling, quoted in Nation, p. 511. Nation and Universe is comprised of two lectures delivered by Walzer at the Brasenose College of Oxford University in 1989.

Keep ye the law—be swift in all obedience—

Clear the land of evil, drive the road and

bridge the ford.

Make ye sure to each his own

That he reap where he hath sown.

By the peace among our peoples, let men know

we serve the Lord.

Kipling (1865-1936) lived in the heyday of the British Empire, whose Union Jack never set. Born in Bombay to a native English couple who belonged to the highest Anglo-Indian society, what did he think of the British rule in India? Would he consider the British rule as occupation and exploitation? The answer is an absolute “No.” As a journalist, poet, and novelist, Kipling celebrated the British imperialism. His chief writings, to borrow the words of a biographer, “were bound up with a genuine sense of a civilizing mission that required every Englishman, or more broadly, every white man, to bring European culture to the heathen inhabitants of the uncivilized world.”42J. I. M. Stewart, Rudyard Kipling, in Encyclopaedia Britannica (2002). CD-ROM. Italics added. This statement makes sense only to some Englishmen and white men. To those peoples who have been conquered and exploited by the British Empire, it explains nothing but adds insult to injury. I think Kipling did not, or dared not see the covered and deep down hatred of the Indians. What he saw was the admiration of some Anglophile Indians for the English technology and for their high society.43The Indian novelist Arundhati Roy discloses the local name of the British Anglophile as chhi-chhi poach, which in Hindi means shit-wiper. See A. Roy, The God of Small Things, London, 1997, p. 51. Kipling’s imperialist persuasions were widely circulated among the Englishmen, especially among the British soldiers in India. The other Europeans, perhaps, while admiring the achievement of the Englishmen, were moved by Kipling’s convictions, at least before the First World War, and awarded him a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907.

Imagine the scene when the “Song of the English” is being sung by marching English adventurers and soldiers. They are marching to stamp out evil, and they will continue until peace is established throughout the world. They know the law and are sent by the law. “Make ye sure to each his own That he reap where he hath sown.” The commission is clear enough and each has to strive for his own salvation. History will only end when all the nations would serve the Lord. Right now, we are the agents of the future peace. Let’s build roads and bridges so that missionaries and soldiers could reach every hinterland. Law will be enforced and civilization secured. Peoples of all places will praise the Lord in peace under the Union Jack. This is a beautiful conviction that every noble nation is more than ready to accept. Sincere? Yes. Tyrannical? More so. The Englishmen did bring their “civilization” and their law to the conquered lands. Some of the establishments might even be helpful to the indigenous peoples. Nevertheless, the native history and autonomy were devalued: the “uncivilized” people were treated as if they did not know what was good for themselves and that they had to learn the law, by force if necessary. Indeed, people were coerced to serve the Highest Majesty. Each conquered nation became a cog within the mechanism built by and for the British Empire. Subjection and exploitation followed and stood side by side with coerced civilization, as they always are.

C. Reiterative universalism

Being a Jewish American, Walzer is sensitive to the diversity of cultures and experiences. It is obvious to him that each nation has developed its particular way of living, and that its people value their creative particularities. No doubt, some of their behaviour and costume may seem strange and incomprehensible to outsiders. These, however, cannot simply be brushed aside as tribal, uncivilized, or irrational. One who disparages the experience of other people and imposes one’s culture against the others’ will acts like a tyrant. Though many universalists are ready to tolerate queer custom in trivial matters, they are unwilling to compromise in serious matters like justice, law, and social institutions. Seeing themselves as the vanguard of human dignity, the universalists take it as their responsibility to defend the universal standards. Their motive may be respectable but their attitude is arrogant and their act despotic. The gravest consequence is that their argument can be exploited by aggressive régimes to cover their aggression. Despite these, Walzer does not want to renounce universalism, because he still recognizes some universal or “almost universal” values shared among different societies.44Interpretation, p. 24. He opts for a minimalist universalism, which he deems would leave the largest room for creative plurality. He proposes a reiterative universalism as an alternative. This reiterative universalism consists principally of a minimal core of moral codes—a set of abstract conception of human values. It assumes that each nation has elaborated the core into particular social institutions and practices. To defend his reiterative universalism, Walzer offers two arguments, a theological one and a philosophical one. Although Walzer is not a trained theologian, he tries to provide a theological argument, for he is very aware of the fact that the theological argument for the covering-law universalism is pervasive, perhaps even more persuasive than its philosophical counterpart. His main concern is to offer a plausible alternative interpretation of the Bible rather than to offer a definitive statement.

1. Theological argument

The covering-law universalism championed by Christianity is characterized by triumphalism. This sense of triumph has something to do with the experience of the Christians. In the Roman Empire period, the Church successfully converted a large number of people to Christianity and gradually became dominant in the Empire. The triumphant church tended to forge its theology in the form of a covering-law universalism so that the whole population would fall within its jurisdiction. Thus said, it implies that the covering-law universalism is not the only interpretation of the Old Testament—there are other possibilities. A Jewish biblical scholar, Jon Levenson, writes that “there is no one ‘biblical’ position on this or on most other great theological issues.”45J. D. Levenson, The Universal Horizon, p. 145. Since the Bible is an anthology of writings composed over a long period, in different places, and by different authors, we really cannot expect it to present a unified view on a particular matter. The universality of the deity, besides the covering-law version, has been developed into the universality of humanity whereby every human being has equal access to the knowledge of God, or into a theology of nation-states whereby God deals with each nation separately.46Cf. J. D. Levenson, The Universal Horizon, pp. 142-151.

Walzer is prepared to exploit the diversity of the biblical texts, and he argues that the universality of the deity does not warrant the universality of the moral norm. One obvious example is Judaism, which is allegedly charged with clannishness. He reasons that while God can be the creator of the universe, he needs not care about all his creation in the same way or in the same measure. It is not difficult to imagine that God favours human beings, who are made in his own image, over animals, or that God chooses one nation as the recipient of his special favour and forgets the rest, or that God prefers one person to another, as is recorded in the Book of Genesis that God has more regard for Abel than for Cain.

A reiterative universalism is proposed by Walzer as an alternative: a universal God hates oppression generally, but he has individual plans for the liberation of each nation—a unique one for each unique nation. It is a universalism devoid of triumphalism and in peace with the particularism of other peoples. Walzer asserts that this is the true doctrine in the Jewish history. It was repressed when Judaism was in full-scale conflict with Christianity. However, this reiterative universalism can be recovered from biblical fragments.47Nation, p. 513. In the course of defending his case, Walzer cites four biblical passages. We will look into them one by one.

Are ye not as children of the

Ethiopians unto me, O children

of Israel? …

Have I not brought Israel out of the

land of Egypt,

And the Philistines from Caphtor,

And the Syrians from Kir?

These questions are probably a starting point of Walzer’s questioning of the standard covering-law universalism. By putting Ethiopians, Philistines, and Syrians on a par with Israel, Amos poses a serious challenge to the Christian doctrine of one God, one people, one law, and one redemption. He suggests the possibility that there might be more than one liberations and salvations. The unique God, who is the creator of the universe, finds oppression universally hateful, and he uses liberation as his universal method of salvation. He delivers people from the land of slavery whenever they cry to him. He sets them free and gives them a unique identity. In this way, he helps fashion the nations. He is not only the creator of people but also the maker of peoples. Walzer calls this paradigm—one liberator, one pattern of salvation, but many particular liberations—“reiterative universalism.”

The main characteristics that distinguish reiterative universalism from the covering-law universalism are its “particularist focus” and its “pluralizing tendency.” “We have no reason to think,” Walzer says, “that the exodus of the Philistines or the Syrians is identical with the exodus of Israel, or that it culminates in a similar covenant, or even that the laws of the three peoples are or ought to be the same.”49Nation, p. 513. In other words, it is possible that each people experiences its own exodus, enjoys its particular divine relationship, and strikes a specific covenant with God according to their specific circumstances. This understanding is congruent with the God who liked Abel but not Cain, and who, out of one man, made all kinds of human beings. If anyone still inclines to think that God has designed only one salvation and one law for all nations, and that every exodus is but an enactment of the same plan, the diversity of histories must render his or her argument implausible.

A second text which speaks the same message but in a more elaborate and dramatic way is found in the Book of Isaiah:50Is 19,20b-25. Cf. Nation, p. 514.

For they [the Egyptians] shall cry unto the Lord because of the oppressors, and he shall send them a saviour, and a great one, and he shall deliver them. And the Lord shall be known to Egypt, and the Egyptians shall know the Lord in that day, and shall do sacrifice and oblation; yea, they shall vow a vow unto the Lord, and perform it. And the Lord shall smite Egypt: he shall smite and heal it: and they shall return even to the Lord, and he shall be intreated of them, and shall heal them. In that day shall there be a highway out of Egypt to Assyria, and the Assyrian shall come into Egypt, and the Egyptian into Assyria, and the Egyptians shall serve with the Assyrians. In that day shall Israel be the third with Egypt and with Assyria, even a blessing in the midst of the land: Whom the Lord of hosts shall bless, saying, Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel mine inheritance.

The immediate context of the parallel text in the Book of Amos (9,7) makes it clear that the purpose of this verse is to rebuke the Israelites for their pride. We may take the above text as serving the same function. The Israelites are proud of themselves as being the elected, the chosen people of God. They have the law and the covenant, and they know God. By contrast, the Gentiles are excluded from the commonwealth; they do not know God and are hopeless. The prophets, however, reprimand the Israelites by pointing out that they are no better than the Gentiles whom they despise. Yes, they know the law, but they do not keep the law. Their conduct is not noticeably better than the Gentiles. They might even commit crimes that are abhorred by the Gentiles themselves. After all, Israel is not all that special. God is the creator of all, and He attends to all peoples. The Egyptians will cry to the Lord because of oppression. And the Lord will send them a saviour, even a great one, to deliver them from suffering. The Lord will make a covenant with them, and they will serve the Lord. The Egyptians will enter into an intimate relationship with God just as the Israelites. Not only will the Egyptians be called but also the Assyrians. In that day, Israel will be but the third with Egyptians and Assyrians.

What inference can we draw from all these? The inference can be drawn from them is—that there is not only one single mediator or representative of God on earth but many. How should we then interpret the historical event of Israel’s exodus? From the covering-law universalist perspective, it is made, Walzer says, “pivotal” in a universal history, “as if all humanity, though not present at the sea or the mountain, had at least been represented there.”51Nation, p. 514. It was done once and for all. The experience and the consequences of the Exodus belong to all. There is no need for other peoples to reiterate the process of liberation. Or if they wish, they can imitate the Exodus with insignificant deviance. Another view, Walzer suggests, takes Israel’s exodus as “exemplary.” It is pivotal only in the particular history of Israel. As for other peoples, it serves just as an example after which they can, if need be, repeat in their own ways. There is no obligation for them to repeat it. If they see it good to reiterate it, there is no requirement for them to do it in exactly the same way as the Israelites. Voluntary reiteration makes a big difference from compulsory imitation. Instead of one universal history, we will have a series of histories. All peoples can find values in their own particular history and live a meaningful life.

Possibly, believers of monotheism might find it not so easy to contemplate reiterative universalism. The two above-mentioned fragments, indeed, only spring up occasionally in a history overshadowed by the covering-law universalism. They suggest an alternative possibility. But they are quickly discarded, repressed, and forgotten. Ironically, what seems unlikely to man is a lively possibility to the all-mighty God, who is active in human history and compassionate about human suffering. We do not have a single reason to restrict a god who is omnipotent, omnipresent, and all-merciful to bestow special favour on one nation and to mandate all the rest of the peoples to follow the path of the chosen one. But if this is the case, it would only be made possible by coercing the non-elected, either by God himself or through the chosen nation. Is God not evenhanded and merciful to all men everywhere? Let us hear the following message from the prophet Jeremiah:52Jer 18,7-10. Cf. Nation, p. 516.

At what instant I shall speak concerning a nation, and concerning a kingdom, to pluck up, and to pull down, and to destroy it; If that nation, against whom I have pronounced, turn from their evil, I will repent of the evil that I thought to do unto them. And at what instant I shall speak concerning a nation, and concerning a kingdom, to build and to plant it; If it do evil in my sight, that it obey not my voice, then I will repent of the good, wherewith I said I would benefit them.

Obviously God is fair to all nations. He recognizes them one by one and deals with them individually, whether in punishing them or in blessing them.

Yet the covering-law universalists might argue, though God institutes or permits the multiplicity of nations on earth, would it not be possible that God judges every one of them by the same standard?53The separation of humankind, according to the Bible, is an act of God. “And the Lord said, ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.’ So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth (Gn 11,6-9, RSV).” Is God’s “voice” not always the same? Is it not the case that the phrase “evil in my sight” refers to one set of evil acts? Though many nations are there, and many liberations might exist, it is still possible that one single set of universal laws covers them all. Walzer, however, thinks it unlikely for two reasons. First, if God makes a particular covenant with each nation separately and blesses each differently, it makes better sense to suggest that he also holds each nation to its own standard. Each nation will then have a unique set of laws, though some evil acts in the sets of laws will most likely overlap. Second, even if there is only one set of evil acts like that of murder, betrayal, and oppression, it is still more probable that there are multiple sets of good, for good is not simply the opposite of evil. We find it relatively simpler to define an evil act such as murder, and to prescribe the prohibition of “Thou shall not kill.” But it takes endless expositions and papers to elaborate the commandment “Love thy neighbour.” Love comes in various modes and in different intensity. It is always possible to have different kinds of love for the neighbour. That is why Jesus instructed his disciples to love their neighbour as themselves. “In either of these views,” Walzer concludes, “God is himself a reiterative universalist, governing and constraining but not overruling the diversity of humankind.”54Nation, p. 516.

The fourth biblical fragment quoted by Walzer is the most daring one. It challenges the faith of monotheism:55Mi 4,4-5. Cf. Nation, pp. 516-518.

But they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree; and none shall make them afraid: for the mouth of the Lord of hosts hath spoken it. For all people will walk every one in the name of his god, and we will walk in the name of the Lord our God for ever and ever.

The last sentence of the above text from the Book of Micah plainly states that each nation will follow its own god. It implies a plurality in the divinity—not that there are three persons within the godhead, but that there are other gods besides Yahweh, as many as the number of nations are. We are not told of their order or hierarchy. Possibly they have different rankings according to their capability. But nevertheless they can maintain a certain balance of power and make peace among themselves in heaven or heavens so that each of them can recruit his own rank and file on earth. Perhaps, the plurality on earth is best explained and justified by a plurality in heaven. This interpretation, Walzer points out, is completely unwarranted in Judaism, which can never accommodate any gods other than Yahweh. Why does this verse appear in the Hebrew Bible? A common response is to attribute the verse to the survival of some earlier belief that each people had its own god when the world was still in the stage of polytheism. After the ancient Jews had advanced to the stage of monotheism, they dropped and repressed such belief. But this answer does not satisfactorily explain the survival. The successive monotheist editors would have easily erased this heretical verse from the holy book. Why did they preserve and incorporate it in the course of editing until it gained a permanent place in the final text? Walzer hints that the verse is not a survival of early polytheistic belief. The first verse (4,4) and the second verse (4,5) are connected by the Hebrew conjunction כִּי, which indicates that they are parallel verses. Together, they constitute a complete sentence. The word כִּי can denote a causal relationship “for.” If that is the case, then the happy “sitting” in the first has to be the consequence of the plural “walking” in the second. All people sit peacefully, everyone under his vine or fig tree, because all people walk, every one of them, in the name of his god. Walzer conjectures that this is the meaning of Micah. Pluralism inspires tolerance, and tolerance makes for peace. “How many of us,” Walzer asks, “will sit quietly under our vines and fig trees once the agents of the first universalism go to work, making sure that everyone is properly covered by the covering law?”56Nation, p. 517.

Pluralism on earth does not necessarily require pluralism in heaven. It needs only a plurality of God’s name on earth: “every one in the name of his god.” The names are different but they all refer to the same God. As there are many names for the same Yahweh in the Hebrew Bible, why can’t other people invent their own names for God? God creates men and women in his own image, and every one of them becomes a different individual. How is this creative aspect of the imago dei reflected in human activity? Authors like to write their own books, painters their own paintings, philosophers their own accounts of the good, and theologians their own names of God. “What human beings have in common,” Walzer writes, “is just this creative power, which is not the power to do the same thing in the same way but the power to do many different things in different ways: divine omnipotence (dimly) reflected, distributed, and particularized.”57Nation, p. 518. If God is the creator and he makes man in his own image, he should be happy with the plurality human beings produce, shouldn’t he? Even though not every book is readable, nor every picture beautiful, nor every ethic good, nor every name appropriate, God has to put up with these as he clearly knows that no human creation is perfect as his is not perfect too, at least from the perspective of human beings. After all, human beings are only his particularized images.

2. Philosophical argument

In the Western tradition, humanity is taken as everywhere the same, and thus men and women are put under the same moral law. However, philosophers are not so ignorant as to be unaware of cultural differences. In order to account for the differences, the universal law is said to be adapted to particular circumstances, and consequently cultural differences can be perceived as variations of the single law. The philosophers’ aim is to maximize commonalities (at least conceptually) and to minimize differences. This singular universalist way of thinking, Walzer opines, will unavoidably stifle cultural creativity and national autonomy. He does not believe that the lessening of control over creativity will inevitably lead to a state of chaos. He tries to propose an alternative model, one that consists of a core morality which can be differently elaborated in different cultures.58M. Walzer, Moral Minimalism, in Thick and Thin. Moral Argument at Home and Abroad, Notre Dame, IN – London, 1994, 1-19, p.4. For him, the idea of elaboration is better than that of adaptation because it takes into consideration human creativity as well as practicality. Moreover it comes closer to the diversity that both anthropology and comparative history have revealed. Since the idea of reiterative universalism is developed gradually over a long period of time, a historical approach may best clarify Walzer’s position on the subject and explain some seeming contradictions in his conceptualization of universality and particularity. However it may appear to be somewhat repetitive as we attempt to present chronologically the variations of Walzer’s ideas.

a. A universalist particularism

Walzer published his first major ethical treatise Just and Unjust Wars in 1977. It has since been widely praised, even by the covering-law universalists. This is partly due to the fact that the book is a marvellous work and partly because the universalists are misled by its universalist overtones with the result that they overlook its particularist foundation. In fact, a tension between universality and particularity is hidden in the book. On the one hand, Walzer assumes that nations in the long history of conflict have developed some common rules of fighting, which can be expressed by the modern idea of rights. These commonalities are taken as the evidence of the existence of universal human values. Walzer, on the other hand, approaches war inductively by extracting general principles from historical cases. A historical event, however, is a particular incident. How can a particular event be universally relevant across time and space? How can his cited examples have universal significance? Like any other inductive method, Walzer’s argument is, at best, provisional. This problem may be dismissed, as many philosophers do, by asserting some commonly known moral principles, say human rights, as a priori universal truths. But Walzer chooses not to dismiss it lightly. He admits the limitation of his methodology, and states frankly that his argument is inconclusive.59M. Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars. A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations, [New York, NY], Basic Books, 21992, p. xxviii. All he attempts to do is to argue for a case. He states explicitly that the right to life and the right to liberty are two assumed universal truths. These assumptions appear to him to be the best way to interpret the morality in war. Nevertheless, he regards these rights as phenomenological rather than metaphysical truths—life and liberty are inviolable not because God has ordained them or they are intrinsically inalienable but because we human beings value them.

Apparently, the Wars is a defence of some universal truths about war: self-defence is always right, aggression is always wrong, killing non-combatants is always a crime, etc. Moreover, the first chapter is devoted to the refutation of realism and relativism. Is Walzer not a universalist? Ironically, he is frequently accused of being a relativist. One easy way to resolve this contradiction is to say that Walzer is both a universalist and a relativist. He is a universalist in international affairs such as war, but a relativist in other matters of morality. Before passing our final judgement, let us investigate some concrete evidence.

In the preface to the Wars, Walzer explains his approach to the morality of war as follows:60Wars, pp. xxix-xxx. Italics added.

There is a particular arrangement, a particular view of the moral world, that seems to me the best one. I want to suggest that the arguments we make about war are most fully understood … as efforts to recognize and respect the rights of individual and associated men and women. The morality I shall expound is in its philosophical form a doctrine of human rights … At every point, the judgements we make (the lies we tell) are best accounted for if we regard life and liberty as something like absolute values and then try to understand the moral and political processes through which these values are challenged and defended.

The morality of war that Walzer attempts to expound is the philosophical doctrine of human rights, or more specifically the right of life and the right of liberty. He will use the notion of rights, which seems to him to be the best ground, to understand the moral world of war. He will take the rights of life and of liberty as a hermeneutical key to interpret the morass of historical cases. Now, the doctrine of human rights is universal. Its claim is that it is applicable to every being who is recognized as human anytime and anywhere. It is a version of the covering-law universalism. Does Walzer accept the covering-law universalism?